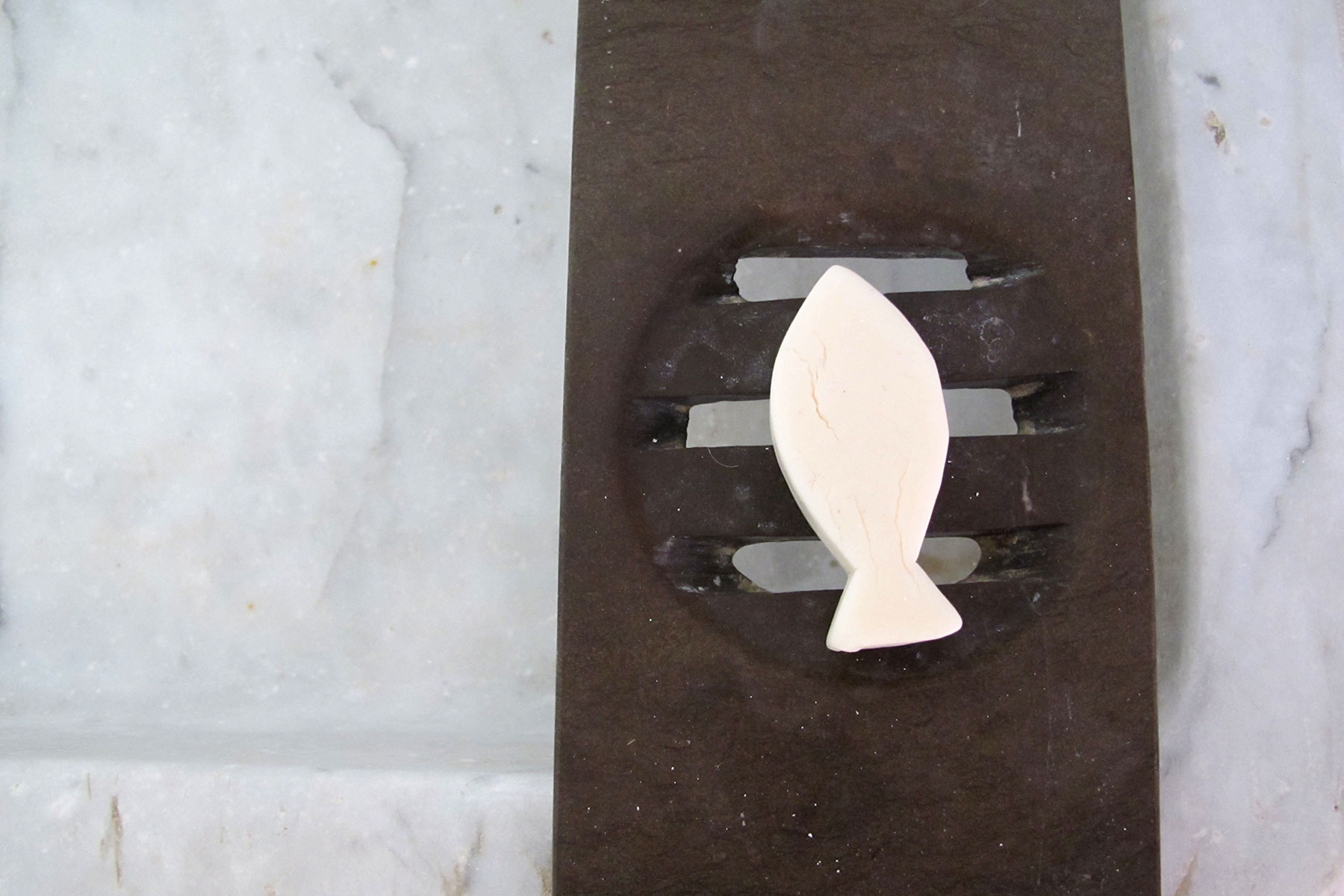

Traditional Arabic architecture doesn’t give a lot away, with vast, exquisitely decorated spaces secreted behind heavy doors and shutters, and guarded further by blank-faced, whitewashed streetscapes. But stay at La Chambre Bleue, a B&B in a vibrant though totally untouristed enclave of Tunis’ ancient Medina, and such a space is yours to temporarily call your own, to slowly gaze upon and absorb. Pre-Jasmine Revolution Tunisia was all about package tourism, where travellers headed directly to the huge resorts along the coast for a sun holiday, only venturing into the capital’s medina perhaps on a shepherded day trip to the souks. But things have begun to change. A band of tenacious independent hoteliers and guesthouse owners kept the faith in the lean couple of years after the revolution, and as visitors return are forging an entirely new kind of travel experience. We talk to Marouane ben Miled, who along with Sondos Belhassen, welcome guests into a beautifully bohemian family home, giving them an insight in the moods and rhythms of daily Tunisian life, as well as a stylish, deeply evocative, place to stay.

Can you tell us a little about how you came to live where you do, and also how you decided to open your home to guests?

We bought our house in 1996. It’s a part of an ancient palace, in Tunis’ Medina. The major part of the palace was abandoned after being separated into different parts; the central, domestic part was destroyed and newly rebuilt, as was the garden; with the goal to save and to live in it, we bought the 19th-century guest apartments and the medieval stables below. After more than ten years of restoration work, interrupted by periods where we didn’t have money to do more, we decided to open the house to guests. In the beginning, for friends-of-friends, for months or more. But since the end of 2009, we made a web page and began this new activity: a B&B, with one room first – la chambre bleue – a former salon, and for one year now, a second room in the former stables.

You both have significant careers outside of running the B&B; what have your respective backgrounds invovled?

Sondos is an artist; she used to dance and was a choreographer of contemporary dance. Now she’s still teaching dance, but is also having a new career as an actress. She’s really an amazing interpreter when she acts or dances. She has done some work of plastic art too, so you can easily understand how she fused the historical building with a contemporary style, in a coherent way. I’m a historian of science and epistemologist. I’m working on Medieval Arabic mathematics, linked with Greek mathematics. So, through my work, I have an interest with the heritage – patrimoine. And, in my family, we have some links with the old stones: we grew up in the Medina, in an old house that my father, a film director, restored, he did the same with a second house too; my two uncles are architects, my aunt used to be archaeologist. So, it isn’t surprising if my brother and I are now living in such houses.

Can you describe briefly the history of the house? The guestroom is, literally, a chambre bleue, a blue room. Is there any significance to the colour blue?

In the 19th-century, families of scholars and high-ranking government officials inhabited this area of the Medina. This palace was a part of a bigger one, owned by the Minister of War, named Mustafa Agha, a former slave of the Bey, who was originally from Georgia. What is really incredible is that when Sondos, who is a direct descendant of Agha’s, joined me in this house, she didn’t know its story. A blue-tiled room of almost 40sqm was traditionally used to receive guests, so, we turned it back to its original task. The colour blue has a story in Tunisia. Originally it was rarely used in crafts or architecture. Old sayings reveal it used to be an unloved colour: we still say ‘a blue night’ for ‘a sleepless night’, and we talk about ‘a blue misfortune’ etc. But, blue became fashionable in the middle of the 19th-century – there’s a legend about it. A tailor bought a large piece of exquisite blue Syrian silk, but he complained to one of his friends that, although the material was beautiful, no one would want to wear a blue costume. This friend was known to be very elegant…he proposed to the tailor to cut him a jebba with its three vests from the silk. And so he launched the blue fashion. I’m not sure the story is true, but it would be nice if it were! The eruption of blue is, in fact, linked to the ‘Movement of Reforms’ of the Tunisian state during that period, which Mustafa Agha was a part of.

So what is happing in the stables?

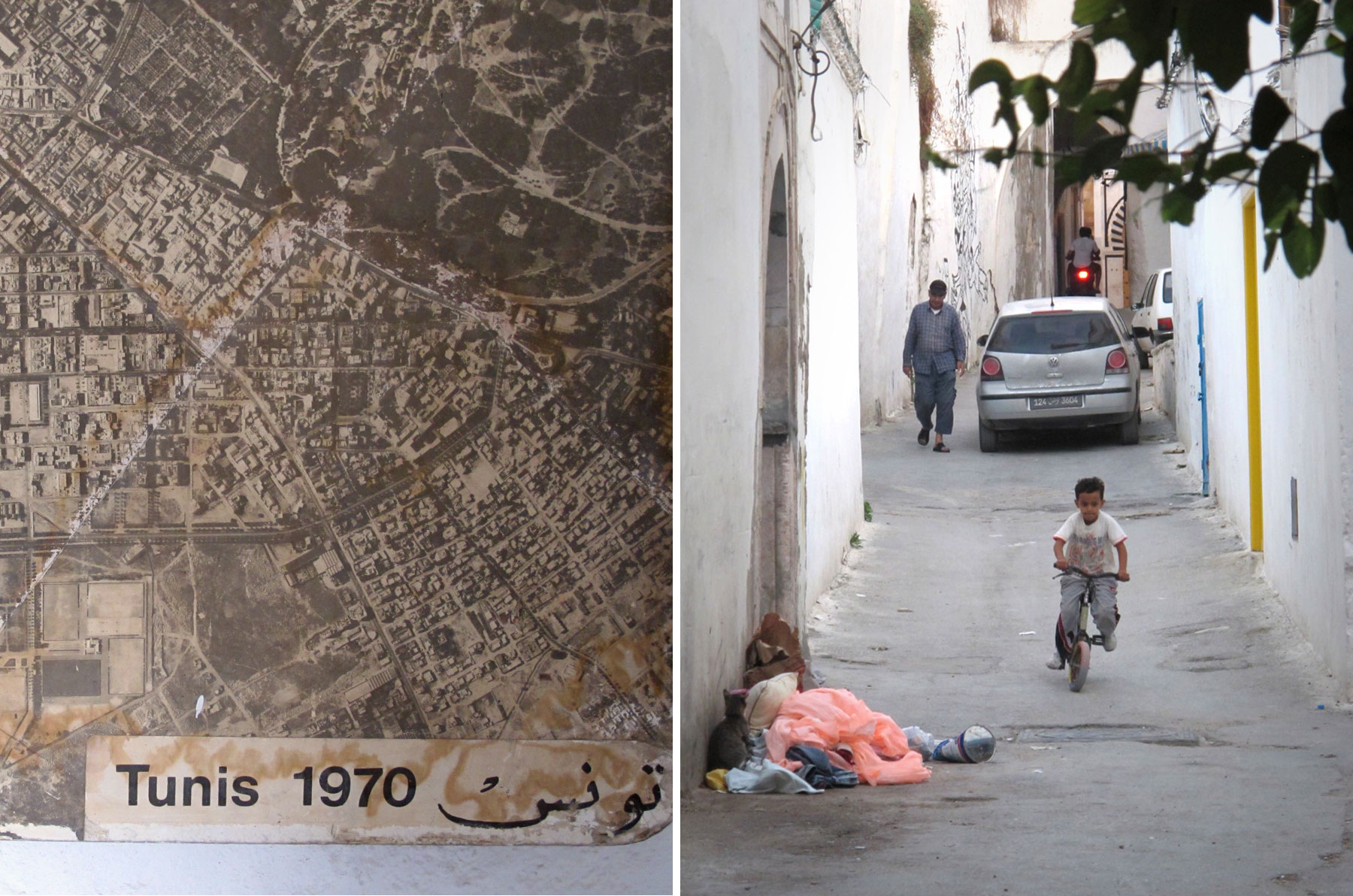

We’ve recently finished the restoration of almost all three stables. Two of them are 13th to 14th century, what is called the Hafsid period. We can date them by their pillars and the style of the local hammams, which gives us the period of this district. The third part dates to the 17th-century. When we were restoring it, we found a squared well under a wall. Square wells are pre-Islamic, meaning it’s Roman or Punic/Phonecian, as after those periods they became circular. We’re using it to refresh the house in summer, for a system of brumisation. One part of the stable is now a library and study for me – I’d like to occassionally open it to the children of the neighbourhood to present scientific experiments. The second is a room we rent to guests. Sondos choose to decorate it in a very contemporary and simple minimalist way, as the room is made up of one central pillar, four arches and four vaults. The third room is still in progress. It isn’t easy to find good artisans for the works, that’s partly why it takes such a long time to finish.

Your neighbourhood is very residential and traditional; how did your immediate community react when you started receiving guests?

Maybe some of the neighbourhood doesn’t understand what we’re doing at all, but they’re accustomed to meeting strangers… as you know Tunisia is a touristic country. And we have to say, that some actually followed us in opening their houses to guests. We’re happy for that and, with some of them, we gave a hand. For us, it is very nice to meet different people from all over the world. It isn’t only a way to have the money to restore the house. We’re happy to share our project, and also to share what is really our city and what is Tunisia, as well as share how we live and think in our country. And the guests who come to stay understand that, and are happy to share it with us. There’s a natural selection with our guests, it isn’t just anyone who decides to travel in Tunisia through BnBs in families’ houses, in the centre of the Medina, while Tunisia is more known for its big cheap hotels on the beach.

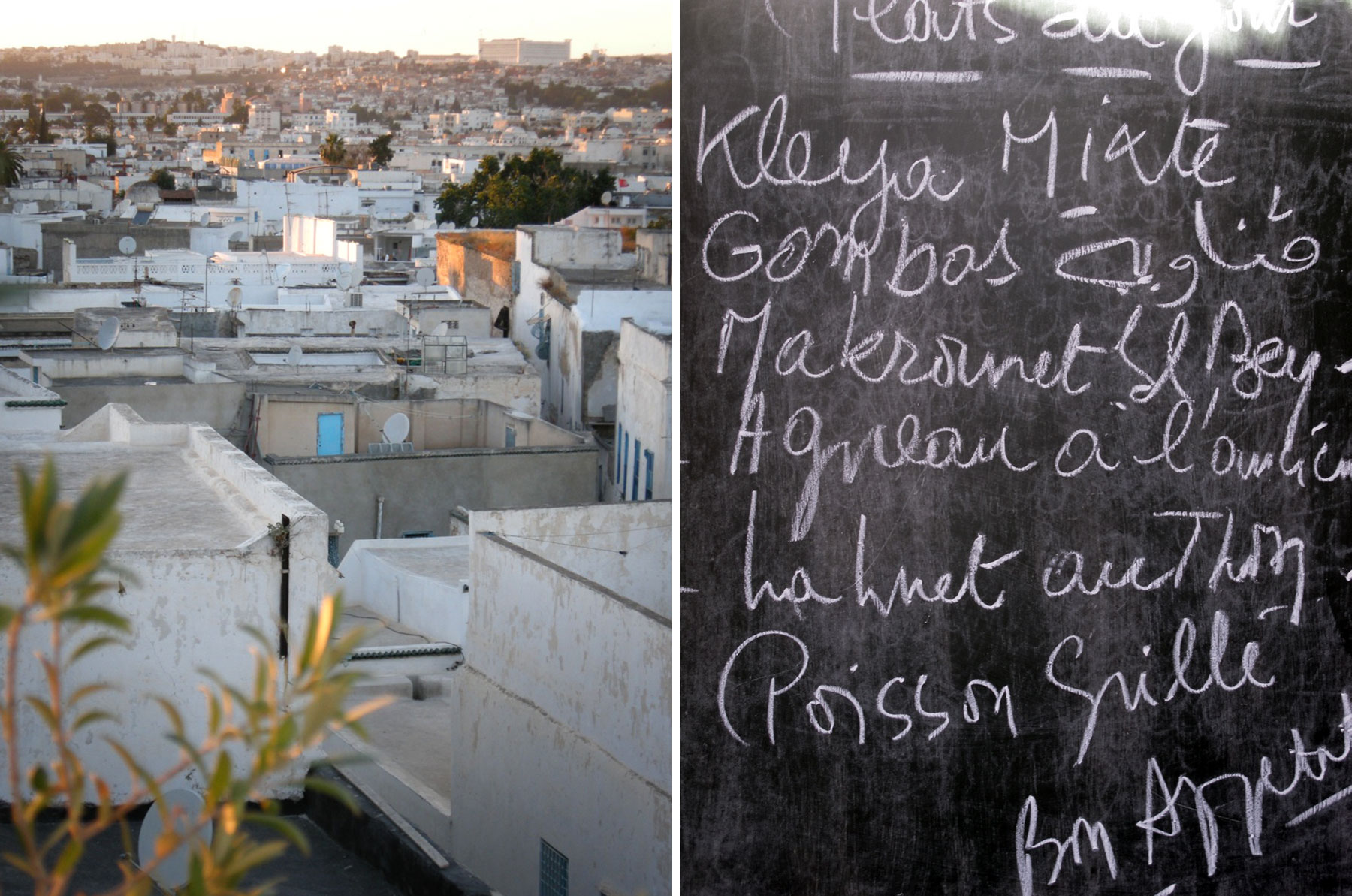

Despite some obvious inappropriate development, the Medina has survived pretty much in tact, no?

The Medina is Tunis, I mean the historical part of Tunis before it extended out of walls in the second part of the 19 th century; this happened even a little before the French Protectorate. After Independence in 1956, the French, along with the large Italian and Maltese population, all left Tunisia. Not long after, so did the Jewish community, with it’s many layers reaching back to ancient times, then the 14th-17th century Andalusians and the Italians in the 18th century. A lot of Tunisians chose to move to the newly empty French houses in the newer districts, leaving these, more or less, well-to-do houses and palaces. In the same time, Tunis saw a rural exodus of poor people who settled in the Medina. The consequence was dramatic for the town, but it’s still, however, on the Unesco’s World Heritage List. For maybe ten years, this movement is reversing and I think we can be optimistic for the future, even if the destroyed houses can’t return and if there is still so much to do.

I remember you telling me about what happened in the height of the uprisings in 2011, and how the Medina almost functioned autonomously, in the way an ancient city may have; can you explain this?

The medieval-age urban organisation of the Medina is what gives this feeling of safety. In these small and thin curved streets, you feel as in a matrice. What happened in the first weeks of the revolution was that the police couldn’t pursue people in these narrow streets. And after Ben Ali’s escape, when his presidential corps tried to create a panic in the population, the army defended the main streets and avenues, while the people defended their own districts.In the Medina, it was easy for us to close our streets and to control who could come in by night. No one was injured here.

Your interiors are a very evocative – a wonderful, vibrant mix of contemporary pieces and local antiques combined with traditional architecture; do you think your style is an expression of a broader ‘Tunisian Modern’ style or trend? Or is it unique to your family and this house?

You know, these houses have always known a lot of change, flux. The past is not such a static thing as we usually think. The 17th and 18th century produced the coloured ceramic ceilings, the 19th the blue colour, the big mirrors, some Italian motifs and the French ‘Empire’ furniture that became fashionable everywhere. In the 20th century, electricity, gas and tap water entered homes. I don’t think it would be a good idea to make our home some kind of museum. What is important is to respect the structure and some of the built-in furniture, and things such as the painted ceilings. And we soon found that the house’s big volumes, high ceilings, the original mix of colours etc, allow the house to accommodate all the choices – classic, vintage, modern and contemporary – we made.

I’ve always dreamed of finding a really great vintage or brocante shop in Tunis…did you source the vintage furniture locally?

Yes, we have some addresses for that, and we also know craftsmen who do some reproduction stuff. Just ask when you visit!

The beautifully vibrant ceramics used for meals also combine traditional techniques and forms with a contemporary eye for simple, bold colour – where are these from?

It’s Hanane Ben Salah’s work, a Tunisian artisan. We can organise for guests to meet her.

Your breakfasts are very memorable!

Sondos tries to create something new for guests each morning. She makes Tunisian pancakes – these are eaten with fresh ricotta and herbed tomatoes. We often add honey to this, so it becomes a sweet dish.

Your whole family are incredibly charming and welcoming…what does it mean to you to constantly share family life with guests?

Thanks! It’s a Tunisian habit to know how to receive guests, but it’s a speciality in Sondos’ family. For us, you know, it’s really sharing; I mean, we receive as much as we give. It’s very nice to meet people from all over the world, and as I told you, the people that choose this way of travelling have something to give too. I have to say that the structure of the house helps – it’s organised around two patios, so it’s easy for us to reserve one for the guests and to live in the other, even if our guests can and do circulate between them.

We spoke in late 2011, in connection to a story I was doing for BBC’s travel site, not that long after the revolution. I remember you expressed a lot of hope, and conveyed a sense that it was a time of great opportunity, both culturally and economically. Things were, I know, really difficult for many hotels, especially the large resorts on the coast, and other businesses that relied on visitors, and have only just started to recover… do you still feel hopeful for the future of independent travel in Tunisia?

Yes, indeed! We’re not alone now, a lot of alternative tourism businesses have opened, some in Tunis’ Medina, but also everywhere in towns and in the countryside. It’s possible now to visit the whole country and only stay in such places. We have organised ourselves through Edhiafa (the Arabic word for ‘receiving’ or ‘welcoming’). A journalist friend – Amel Djaiet – has created a very nice website, Mille et Une Tunisie, that documents the independent tourism scene, and, of course, we now have a new minister of tourism, Amel Karboul, who understands the importance of this kind of culture.

Apart from the new stables room, what else is new?

Sondos is organising joint dinners with another guesthouse in the medina. It’s very nice, because guests can visit another home, meet other Tunisian people as well as other visitors travelling the same way. We cook Tunisian food, usually rare recipes you easily can’t find in restaurants. Guests can also now book to receive a massage and some facial care by a professional.

Speaking of Tunisian food – as you know I’m a big fan – what’s the one dish you’d suggest a visitor should try?

There are so many special dishes! Why not the sadly not well-known couscous of fish with pumpkin and currant (and without tomato!).

What is your favourite thing about the Medina?

The streets, in the middle of the night, when they’re deserted and quiet… especially in the beginning of the spring, when the flamingos cross the sky very low.

- La Chambre Bleue

- 24, rue du Divan Médina de Tunis

- ph. +216 22 57 96 02

- lachambrebleue.net